Opening: Through the Lens of Landman

The opening shots of Landman tell you everything you need to know about West Texas: an endless expanse of flat, scrubby desert stretching to the horizon, interrupted only by the rhythmic bobbing of countless pump jacks—mechanical horses drinking crude from deep beneath the earth. Dust devils swirl across two-lane highways where 18-wheelers loaded with drilling equipment roar past at dangerous speeds. Through the heat shimmer, you can see the orange glow of gas flares burning off excess natural gas, tiny man-made suns dotting the landscape day and night.

Billy Bob Thornton's Tommy Norris drives through this world with the weary familiarity of someone who knows every mile marker, every dangerous intersection, every boom and bust that has shaped this unforgiving land. His truck kicks up dust on roads that connect drilling sites, man camps, and oil company offices—the circulatory system of an industry that pumps not blood but black gold.

But this landscape that looks so dramatic on screen? It's barely scratching the surface of the real story. Because this patch of West Texas desert—known as the Permian Basin—has been the stage for one of the most volatile, dramatic, and consequential economic sagas in American history. A story spanning a full century, marked by spectacular booms that minted millionaires overnight and devastating busts that turned thriving towns into ghost towns.

When we watch Landman, we're seeing just the latest chapter in a cycle that has repeated itself again and again, each time reshaping communities, families, and the very land itself.

Act I: The Forgotten Frontier (Pre-1920s)

Before there was oil, there was nothing—or at least, that's how it seemed to most Americans. The Permian Basin, spanning more than 75,000 square miles across western Texas and southeastern New Mexico (larger than the entire nation of England), was considered among the most inhospitable places on the continent.

The climate was brutal: scorching summers where temperatures regularly exceeded 100°F, winters that could bring sudden ice storms, and a near-constant wind that carried stinging sand. Annual rainfall averaged just 15 inches, barely enough to support the hardy mesquite and creosote bushes that dotted the landscape. Water was scarce. Trees were scarcer.

The few people who called this place home in the early 20th century were ranchers raising cattle on vast spreads where it took 50 acres to support a single cow, cotton farmers gambling against the weather, and small-town merchants serving these isolated communities. Towns like Midland and Odessa were little more than whistle-stops on the Texas and Pacific Railway, their populations numbered in the hundreds rather than thousands.

Young people left as soon as they could. There was no future here, parents told their children. Go to Dallas, go to Houston, go anywhere but here. The land itself seemed to reject human ambition—it was too dry for good farming, too flat for scenic beauty, too hot for comfort, too far from everywhere for commerce.

Christian Wallace, co-creator of the Boomtown podcast that inspired Landman, grew up hearing stories from his grandfather's generation: "Nobody believed this desert would ever amount to anything. It was a place you passed through on your way to somewhere else."

Act II: Divine Intervention—The Santa Rita Discovery (1923)

Then came the miracle—or at least, what felt like one. On May 28, 1923, a drilling rig operated by a team of wildcatters struck oil on land belonging to the University of Texas near the tiny town of Big Lake. They had been drilling on a prayer, quite literally: the well was named Santa Rita No. 1, after the Catholic patron saint of impossible causes.

At 1:30 in the afternoon, the drill bit punctured a pocket of oil-saturated rock at a depth of 3,050 feet. Within hours, crude was gushing from the earth at a rate of 100 barrels per day—modest by later standards, but earth-shattering in that moment. The "black gold" that had transformed other parts of Texas was here too, hidden beneath thousands of feet of rock.

Word spread with telegraph speed. Within weeks, speculators, geologists, roughnecks, and fortune-seekers began pouring into the region. The oil rush was on.

Act III: The First Boom and the Birth of Oil Towns (1920s-1930s)

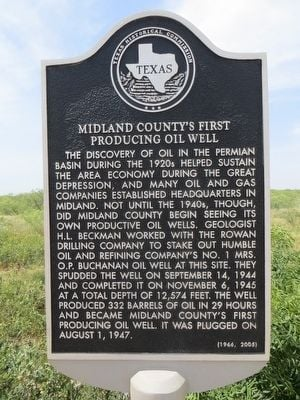

The 1920s transformed the Permian Basin from forgotten frontier to the new American dream. Towns that had barely existed exploded in population. Midland, positioned at the geographic center of the basin with rail connections, became the white-collar hub—home to oil company offices, banks, and the Petroleum Building, an art deco tower that still stands today as a monument to those heady days.

Odessa, just 20 miles west, became the blue-collar counterpart—rougher, tougher, where the roughnecks and roustabouts lived in hastily constructed boarding houses and spent their paychecks in saloons and dance halls. The cultural divide between refined Midland and working-class Odessa was born in this era and persists to this day.

This was the age of the "wildcatter"—independent oilmen who relied on gut instinct, borrowed money, and sheer audacity to drill where major companies feared to tread. Some struck it rich. Many went broke. A few became legends.

Makeshift towns sprang up around drilling sites, complete with their own post offices, general stores, and red-light districts. The region had never seen such money, such energy, such possibility. The boom mentality took hold: spend now, plan never, because tomorrow the well might run dry.

But beneath the euphoria lurked the seeds of disaster. The frenzy led to overproduction. Too many wells competing to sell crude caused oil prices to plummet. By the early 1930s, combined with the onset of the Great Depression, the party was over.

Act IV: The First Bust—Learning the Cycle (1930s)

The collapse was swift and merciless. As oil prices cratered, small operators went bankrupt. Workers were laid off by the thousands. The boarding houses and hotels that had been bursting with tenants stood empty. Businesses shuttered their windows. The land was littered with abandoned drilling equipment, rusty monuments to failed dreams.

Population figures tell the story: towns that had swelled to several thousand residents shrank by half or more within a few years. Those who remained did so out of stubbornness, poverty, or faith that better days would return.

This first bust taught the region a lesson it would never forget: what the oil giveth, the oil taketh away. The boom-bust cycle—the manic oscillation between prosperity and poverty—became baked into the West Texas psyche. It created a culture of cautious optimism, where even in the best of times, people remembered the worst.

The state of Texas responded by implementing production quotas to stabilize prices, giving the Texas Railroad Commission unprecedented power to control how much oil could be pumped. It worked, somewhat. Prices stabilized, but the glory days were gone. Through the remainder of the 1930s, the Permian Basin settled into a quieter rhythm, producing steady if unspectacular amounts of oil.

Act V: War, Revival, and the Golden Age (1940s-1970s)

Then came World War II, and with it, insatiable demand for petroleum. Tanks, trucks, ships, and planes all ran on oil, and the Permian Basin became crucial to the Allied war effort. The federal government poured money into infrastructure—roads, pipelines, refineries. Production soared. The workforce swelled with both returning veterans and migrants from other parts of the country looking for well-paying work.

The post-war decades were the Permian's golden age. American car culture exploded, creating seemingly endless demand for gasoline. Oil prices remained relatively high. The basin produced more than 1 million barrels per day—enough to make West Texas a global player in energy markets.

This was when the region's cultural landmarks were established. High school football became a religion, immortalized decades later in Friday Night Lights. The Petroleum Club in Midland became the beating heart of the region's elite—where deals were made over whiskey and handshakes, where fortunes changed hands on the basis of trust and shared risk.

It was also when a young veteran named George H.W. Bush moved to Midland in 1950 to try his hand in the oil business. He and his wife Barbara bought a house in the East Side, raised their family (including a future president, George W. Bush), and built Zapata Petroleum into a successful drilling company. The Bush family's West Texas years shaped their politics and worldview in ways that would later affect national policy.

The 1970s brought the OPEC oil embargo, which perversely benefited West Texas. When Middle Eastern nations restricted supply, oil prices tripled seemingly overnight. The Permian Basin hit record production levels. New millionaires were made daily. Luxury car dealerships opened. Private jet traffic at Midland International Airport rivaled some major cities. Real estate prices soared.

It felt like the boom would never end. That should have been the warning sign.

Act VI: The Bloodbath—The 1980s Collapse

What happened in the 1980s wasn't just a bust. It was a catastrophic economic implosion that scarred the region for a generation.

The crash began in 1981 when global oil prices peaked around $35 per barrel, then started sliding. By 1986, the price had collapsed to just $10 per barrel—a 70% drop in five years. For an industry with high fixed costs and debt loads accumulated during the boom years, it was apocalyptic.

The devastation was total:

- Major oil companies like Exxon abandoned their West Texas operations entirely, leaving behind empty office towers that stood as tombstones for the industry

- Local banks, overexposed to oil loans, failed by the dozens

- Unemployment in Midland-Odessa reached 20%, among the highest in the nation

- Real estate values plummeted to a fraction of their peak—homes that sold for $200,000 in 1981 couldn't find buyers at $40,000 five years later

- Divorce rates spiked as financial stress tore families apart

- Substance abuse and suicide rates climbed

- By 1986, Midland's population had dropped by nearly 30%

The physical landscape reflected the economic devastation. Strip malls stood empty, their parking lots cracked and weed-choked. "For Sale" and "For Lease" signs proliferated like tumbleweeds. Downtown Midland, once bustling with oil executives in suits, became a ghost town after 5 PM. Abandoned drilling sites dotted the desert, rusting in the relentless sun.

Christian Wallace, who was born in the nearby town of Andrews in the late 1980s, grew up amid this wreckage: "My whole childhood, the town looked like a disaster had struck. Abandoned buildings, empty lots, closed businesses. You'd see old oilfield equipment just rusting in fields because it wasn't even worth hauling away. Everyone knew someone who'd lost everything—their house, their job, sometimes their family. That bust broke people in ways that went deeper than money."

The psychological impact was perhaps worse than the economic one. An entire generation learned that prosperity was a cruel illusion, that planning for the future was fool's gold. The ethos became: take what you can get today, because tomorrow it might all disappear.

Act VII: The Long Decline (1990s-2000s)

Through the 1990s and 2000s, the Permian Basin existed in a state of quiet decline. Oil production continued, but at steadily decreasing rates. The basin was considered a "legacy field"—its glory days were behind it, its best reserves already depleted. Major oil companies shifted their attention to newer, more promising areas: deep-water drilling in the Gulf of Mexico, projects in West Africa and Brazil, the oil sands of Canada.

Young people continued to leave. The population aged. School enrollment dropped. The region's economy diversified somewhat—healthcare, retail, small manufacturing—but nothing could replace the oil industry's dominance.

During these decades, outsiders viewed West Texas with a mixture of pity and condescension. The region became associated with decline, with a stubborn refusal to accept that its time had passed. When locals insisted that oil would come back, that new technology might unlock reserves everyone thought were exhausted, people smiled politely and changed the subject.

What no one realized—not the major oil companies, not the analysts, not even most of the people who lived there—was that a revolution was quietly taking shape. A combination of technologies, perfected in other oil fields and other parts of the country, was about to converge in the Permian Basin.

And when they did, the boom that resulted would make everything that came before look like a warm-up act.

Act VIII: The Shale Revolution—Boom Beyond Imagining (2010s)

The transformation began quietly around 2010, then accelerated with breathtaking speed. The breakthrough was the combination of two technologies: hydraulic fracturing (fracking) and horizontal drilling. Neither was new, but their application to the Permian's vast shale formations unlocked oil that had been technically unrecoverable just years before.

The numbers tell an almost unbelievable story:

- In 2010, the Permian Basin produced about 1 million barrels per day

- By 2018, production had soared past 5 million barrels per day

- By 2020, the basin was producing nearly half of all U.S. crude oil

- This surge made the United States the world's largest oil producer, surpassing Saudi Arabia and Russia

The new boom dwarfed anything the region had experienced before. According to TIME magazine's 2019 investigation, the transformation was visible from the air: "Countless oil wells, identified by their glowing red flames, dot the dark landscape." The basin had become a constellation of industrial activity, visible from space.

The population explosion was staggering:

- Midland's population jumped from 111,000 in 2010 to nearly 180,000 by 2020

- Odessa grew from 90,000 to 160,000

- Smaller towns like Pecos and Monahans saw 30-40% growth in just a few years

But growth brought chaos. The region's infrastructure, built for a much smaller population, buckled under the strain:

Housing: Hotels that once charged $60 per night were suddenly asking $300 and still selling out weeks in advance. Home prices in Midland briefly rivaled those in San Francisco. Developers couldn't build fast enough. "Man camps"—temporary housing facilities with hundreds of beds—sprang up across the region, housing transient workers from across America and beyond.

Traffic: Roads designed for ranch trucks and family sedans now carried thousands of 18-wheelers daily, hauling drilling equipment, water for fracking operations, and crude oil to refineries. Highways 20 and 285 became among the deadliest in America, with fatal accidents occurring weekly. The constant rumble of diesel engines became the region's soundtrack.

Services: Hospitals, schools, police departments, and fire stations struggled to serve a population that had doubled in less than a decade. Wait times in emergency rooms stretched to 8-10 hours. Schools went on double sessions. Crime rates, particularly drug offenses and domestic violence, spiked dramatically.

Labor shortage: With oil companies offering six-figure salaries to roughnecks, every business competed desperately for workers. Fast-food restaurants advertised $15 per hour starting wages plus 401(k) benefits. Gas stations offered signing bonuses. Even truck drivers were making $100,000 per year or more.

The wealth was real and spectacular. Luxury car dealerships opened. Private jet sales boomed. Real estate developers built gated communities with golf courses. Upscale restaurants charged $40 for a steak and still had hour-long waits.

This was the world that Taylor Sheridan and Christian Wallace sought to capture in Landman. Tommy Norris's daily reality—the endless driving, the dangerous worksites, the deals made in dusty parking lots, the precarious balance between profits and catastrophe—was drawn directly from the lived experience of thousands of people navigating this modern-day gold rush.

As one local told TIME: "When it's good, it's awesome." But the unspoken remainder of that sentence hung in the air: And when it's bad...

Act IX: The Shadow of Uncertainty (2020s)

The boom, of course, couldn't last forever. It never does.

On April 20, 2020, the unthinkable happened: oil prices went negative. For the first time in history, producers were paying people to take oil off their hands. The immediate cause was the COVID-19 pandemic, which had crushed global demand for petroleum just as storage facilities reached capacity. But the underlying factors ran deeper: oversupply, shifting energy policies, and the growing reality of climate change.

Christian Wallace, who had been documenting the boom for his Boomtown podcast, recorded a special episode trying to make sense of the chaos: "People in the patch have seen busts before. But they'd never seen anything like this. Oil below zero? It broke something fundamental in how people understood the market."

The crash was sharp but relatively brief. By mid-2021, prices had recovered and production resumed. But the episode left scars. It reminded everyone—from billionaire wildcatters to roughnecks sleeping in man camps—that the ground beneath their feet was never as solid as it seemed.

Today, the Permian Basin faces new uncertainties:

Climate Policy: As governments worldwide implement stricter emissions standards and carbon pricing schemes, the long-term demand for fossil fuels remains questionable. European nations have signaled they may impose tariffs on high-carbon products, potentially excluding American crude from their markets.

Investment Shifts: Major financial institutions have begun divesting from fossil fuel projects, making it harder and more expensive for oil companies to raise capital. ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) criteria increasingly dominate investment decisions.

Renewable Competition: The cost of wind and solar power has plummeted, making renewable energy economically competitive even in oil country. Ironically, West Texas's wind resources are among the best in the nation, and wind farms now dot the same landscape as pump jacks.

The Next Bust: Everyone in West Texas knows another bust is coming. They always do. The only questions are when and how severe. Will it be a 1980s-style catastrophe? Or a more manageable downturn? And crucially: what happens to communities that have once again built their entire economy on the petroleum foundation?

These are the questions that haunt the characters in Landman. Tommy Norris knows the boom won't last. Monty Miller, the oil tycoon played by Jon Hamm, knows it. Everyone in the patch knows it. They just don't know when the music will stop, and they're not ready to leave the dance floor yet.

Conclusion: A Culture Forged in Extremes

After a century of booms and busts, the Permian Basin has developed a distinct culture—one that outsiders often misunderstand but that makes perfect sense if you know the history.

Resilience and Stubbornness: The people who remained through every bust, who rebuilt after every collapse, who refused to abandon their homes even when logic suggested they should—they created a culture of almost defiant persistence. "This is our land," they say, "and we're not leaving." It's a sentiment that resonates deeply in Landman, where characters display a stubborn commitment to place that transcends rational economic calculation.

Boom Mentality: Decades of volatility have taught West Texans to seize opportunities when they appear, because tomorrow they might vanish. This creates a speculative, risk-taking culture where fortunes are made and lost on gut instincts and handshake deals. It's a mentality that values action over planning, courage over caution—exactly the world Tommy Norris navigates in the show.

Pragmatic Morality: When your livelihood depends on an industry that operates in legal and regulatory gray zones, when your community's survival hinges on deals that test ethical boundaries, morality becomes situational. This is perhaps Landman's most controversial but honest portrayal: the recognition that in resource extraction zones, the rules are different, the stakes are existential, and survival often requires compromise.

Distrust of Outsiders: Every boom has brought waves of newcomers seeking easy money. Every bust has seen them disappear. This cyclical migration has created deep skepticism toward anyone without roots in the region. The division between "locals" and "oilfield trash" remains stark, even when both groups are technically in the same business.

Environmental Ambivalence: The people of West Texas understand—perhaps better than most—that oil extraction damages the environment. They see the flared gas, the polluted water, the scarred landscape. But they also see the schools built with oil tax revenue, the hospitals equipped with donations from oil money, the families fed by oil paychecks. It's a moral complexity that simple environmental messaging often fails to capture.

When we watch Billy Bob Thornton's weathered, sardonic Tommy Norris driving through that dust-storm landscape in Landman, we're seeing more than a TV character. We're seeing the embodiment of a century of West Texas history—the boom and the bust, the fortune and the loss, the stubborn refusal to quit even when quitting would be the rational choice.

The story of the Permian Basin isn't over. Production continues at near-record levels. New technologies may unlock even more oil from increasingly marginal reserves. Climate policies may force a faster transition away from fossil fuels. Another crash may be imminent, or the good times may roll for another decade.

But one thing is certain: the cycle will continue. Boom will follow bust will follow boom, as it has for a hundred years. The communities of West Texas will adapt, survive, and when the next bust comes—as it surely will—they'll hunker down, wait it out, and prepare for the next boom.

Because that's what they do. That's who they are.

And when you watch Landman—when you see Tommy Norris exhausted but undefeated, when you see deals made in strip club parking lots, when you see the landscape lit by a thousand gas flares—you're not just watching a TV show. You're watching the latest chapter in an American story that's still being written, one barrel of oil at a time.

What aspects of West Texas oil culture surprise you most? Have you noticed connections between Landman and the real history of the region? Share your thoughts in the comments below, and stay tuned for our next deep dive: "What Exactly IS a Landman? Inside Oil's Most Crucial (and Mysterious) Job."