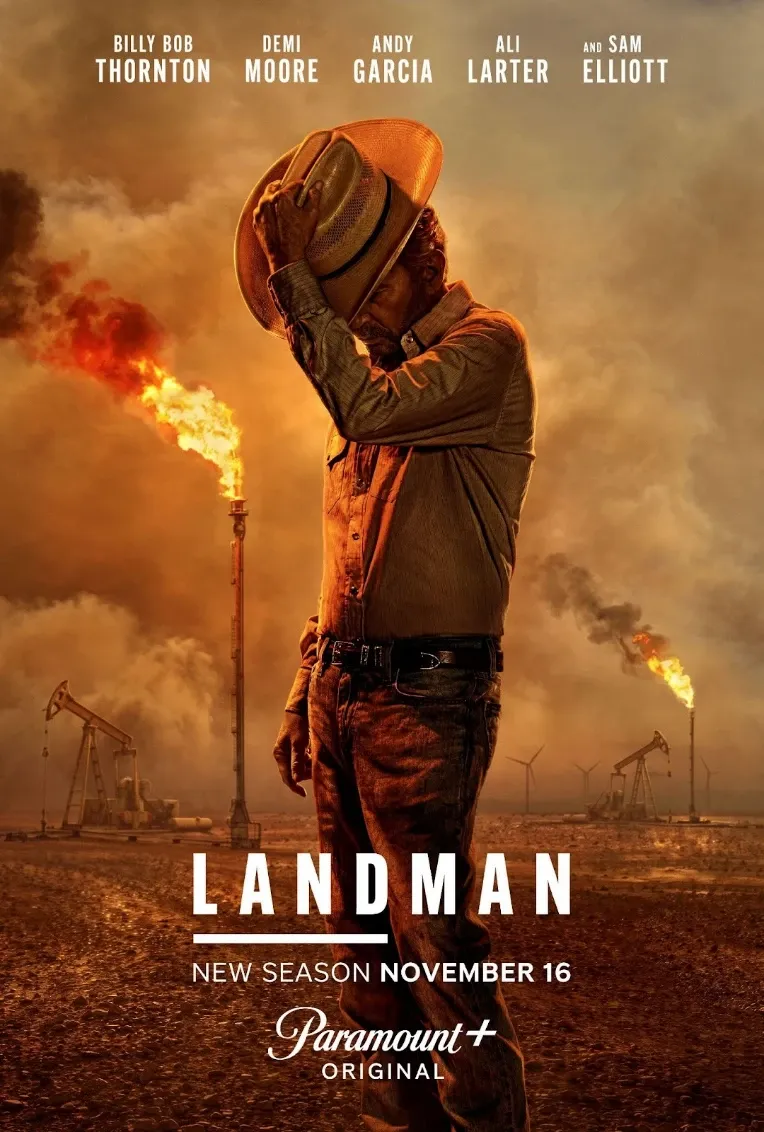

On Sunday, November 16, Paramount+ premiered the second season of Landman, Taylor Sheridan's West Texas oil melodrama, to 35 million global viewers—a number that sounds less like a niche streaming event and more like a cultural referendum. Billy Bob Thornton, back as fixer-patriarch Tommy Norris, already has a Golden Globe nomination for his first-season work. The ten-episode arc returned to its weekly Sunday slot, staking out prime territory against the NFL and delivering Sheridan's signature blend: boardroom brinkmanship, oilfield disasters, cartel tension, and a worldview that treats land, power, and masculine authority as the last honest currencies in a compromised America.

If Yellowstone made Sheridan the most-watched showrunner on television, Landman confirms what that empire actually sells—a glossy, genre-fluid translation of culture war anxieties into entertainment that plays across partisan lines not despite its politics but because of them. The show's second season arrives at a telling moment: as Paramount+, under new ownership, bets its streaming future on direct-to-consumer profitability and Sheridan's middle-American juggernaut, Landman offers a case study in how television metabolizes American decline, resource conflict, and generational resentment into something audiences on both coasts and in between find compelling, troubling, and hard to look away from.

Figure 1: Billy Bob Thornton as Tommy Norris, the oil industry fixer at the center of Landman Season 2. His performance earned a Golden Globe nomination and anchors Sheridan's West Texas melodrama with weary pragmatism and frontier masculinity.

The Sheridan Empire: Eight Shows, One Worldview

By now, the numbers are familiar: eight series, 164 episodes, a portfolio that includes Yellowstone and its period prequels 1883 and 1923, plus Mayor of Kingstown, Tulsa King, Special Ops: Lioness, Lawmen: Bass Reeves, and Landman. Sheridan retains unusual creative control across the slate, and each show, despite surface differences—Texas oilmen, Tulsa mobsters, CIA operatives—returns to the same moral bedrock: land as identity, labor as virtue, institutions as corrupt, family loyalty as law.

Yellowstone, the anchor franchise, became the most-watched show on broadcast or cable by 2022, with executives explicitly crediting its appeal beyond coastal metros. Academic analysis tracks its rise across the "streaming wars" and the "culture wars," noting a claimed 100 million global viewers by 2023 and production costs in the prestige tier. The show's "Y" brand—on hats, on jackets, on ranch gates—functions as both narrative symbol and lifestyle commodity, blurring the line between storytelling and identity marketing.

Critics have labeled Yellowstone as "speaking the language of culture war with a perfect accent," a phrase that captures both the show's ideological fluency and its strategic ambiguity. The series fixates on land not as real estate but as sovereignty, with John Dutton's ranch operating as a moral universe where family loyalty and property protection justify ruthless tactics. The New York Times cautioned against simplistic red-state labeling while underscoring the show's fixation on land as legitimacy and power. The Atlantic, in an essay on Beth Dutton, described how the series turns a real-estate war into a worldview, with "family above all" serving as moral absolution for any action taken in defense of the ranch.

Sheridan's broader slate extends this logic across genres. Lioness and Mayor of Kingstown trade ranch land for geopolitical and carceral power, but the underlying grammar remains: untrustworthy institutions, hard men (and occasionally women) doing necessary violence, monologue-driven moral instruction. Rolling Stone notes his preference for definitive, masculine lectures over contested public arguments, while scholars position his work as populist fables of stewardship against change—a formula that resonates with audiences feeling neglected by prestige TV's coastal tastes.

Figure 2: Official Season 2 ensemble poster featuring Billy Bob Thornton, Demi Moore, Andy Garcia, Ali Larter, and Sam Elliott against oil field imagery. The promotional material emphasizes the show's prestige production values and star power.

Oil as the New Ranch: What Landman Is and How It Works

Landman transposes Sheridan's template from Montana ranching to West Texas petroleum, giving the Permian Basin the "Yellowstone treatment." Tommy Norris, Billy Bob Thornton's swaggering VP of Operations at M-Tex Oil, plays the same structural role as John Dutton: a workingman diplomat navigating between roughnecks in the field and billionaires in the boardroom, translating between labor and capital while keeping his moral code intact. Where Yellowstone romanticizes cattle and horseback, Landman does the same for drilling rigs, mineral rights, and the blue-collar pragmatism of energy extraction.

Season 2 picks up with power vacuum drama: Monty Miller's death leaves Tommy juggling the company, Cami Miller (Demi Moore), and cartel interests led by Andy Garcia's Gallino, now upgraded to series regular. The narrative splits between corporate intrigue and oilfield peril—Episode 3's hydrogen sulfide disaster serves as both visceral set piece and thematic statement about the literal toxicity baked into the industry. Thornton's performance anchors it all, delivering deadpan riffs on modern "sissification" (the season opens with a cornflakes gag about masculinity in decline) while navigating family melodrama involving his ex-wife, his daughter, and generational friction.

Critics agree the show engrosses when it maps the industry's routines and moral ambiguities. NPR praised its oil-field competence but faulted its women; Variety called it compelling when focused on petroleum but frustrating when it veers into family soap. The Guardian, more caustic, described Landman as a "horny throwback" marketed to men feeling culturally sidelined, with its gender politics functioning as comfort food for audiences who find validation in Tommy's one-liner physics and anti-renewables zingers.

The show's visual language reinforces its themes. Pump jacks against vast, empty horizons evoke both frontier mythology and industrial scale; boardrooms shot in cool blues contrast with the warm, dusty golds of the field. The production leans into scale and spectacle—fiery blowouts, cartel violence, helicopter panoramas—packaging labor conflict and resource extraction as prestige melodrama. Sheridan's signature move, as Rolling Stone notes, is turning technical exposition into ideology: a monologue about wind turbines becomes a catechism for oil, delivered with the certainty of a man who knows his audience wants answers, not debates.

Figure 3: Thornton's Tommy Norris in corporate headquarters wearing a cowboy hat with blazer—visual shorthand for the show's central tension between frontier identity and modern corporate power structures. This duality defines much of Landman's culture war coding.

Figure 4: West Texas oil field landscape showing multiple drilling rigs across the Permian Basin. Landman uses this industrial aesthetic to frame petroleum extraction as both economic necessity and frontier mythology, central to Sheridan's thematic architecture.

The Culture War Playbook: Land, Masculinity, Institutional Decay

Landman distills Sheridan's recurring themes into a particularly pure form, using West Texas oil as a vehicle for three interlocking anxieties that track closely with contemporary American political discourse.

First, land and resource sovereignty. Where Yellowstone frames land ownership as moral legitimacy, Landman applies the same logic to mineral rights and energy extraction. Tommy's work isn't just business—it's stewardship of American power, a dirty-but-necessary job that keeps the lights on and the economy running. The show treats oil drilling as a form of patriotism, with renewables positioned as naive coastal ideology disconnected from material reality. One Season 1 monologue, widely circulated online, has Tommy lecturing a young idealist on wind turbine inefficiency and fossil fuel necessity, framing the energy debate not as environmental science but as a referendum on whether America still has the stomach for hard, unglamorous work.

Second, masculinity under siege. Tommy Norris embodies a specific fantasy of competent, unfiltered manhood: he speaks plainly, solves problems with a combination of charm and threat, and navigates a world where women are either unruly chaos agents or sexualized complications. His Season 2 cornflakes gag—complaining that modern cereal brands have been "sissified"—plays as throwaway humor, but it's ideologically load-bearing. The joke, and dozens like it, position Tommy as the last sane man in a world gone soft, offering viewers permission to laugh at anxieties about gender fluidity, political correctness, and the erosion of traditional masculine authority.

Third, institutional rot and the virtue of individual action. Landman, like all Sheridan shows, treats official institutions—government, regulators, HR departments, corporate bureaucracy—as either incompetent or malicious. Real work happens in the field, in back-channel deals, in the spaces where men like Tommy operate outside formal rules. This anti-institutional stance resonates across the political spectrum: progressives see corporate malfeasance, conservatives see regulatory overreach, and both can project their frustrations onto a narrative where the bureaucracy is always the villain and the individual operator is always more trustworthy.

Academic critics note that Sheridan's work updates the Western's classic civilization-versus-barbarism binary into a tripartite struggle among Indigenous nations, resource extractors, and finance capital, with land and sovereignty at the center. Landman simplifies this further: the cartel represents barbarism, the board represents amoral capital, and Tommy represents the embattled middle—the working professional who understands both worlds and trusts neither. It's a structure designed to let viewers locate their own political enemies within the show's moral architecture.

Figure 5: Iconic pump jack against storm clouds—the visual grammar Sheridan uses to code oil extraction as both industrial might and environmental vulnerability. The show treats these machines as symbols of American power and masculine labor rather than subjects of environmental critique.

The Cost of the Formula: Gender, Erasure, and Violence as Style

For all its craft, Landman invites the same criticisms that have trailed Sheridan's work since Yellowstone's breakout success: questions about gender representation, Indigenous erasure, and the aestheticization of violence.

The gender issue is the most persistent. Nearly every major review of Landman notes that its women function primarily as problems to be managed or fantasies to be indulged. NPR called the show "compelling" but faulted its portrayal of women; Variety described Demi Moore's Cami Miller as one of the few characters with agency, yet even she operates within a narrative that codes female ambition as either shrill or seductive. Tommy's daughter Ainsley exists largely to create family melodrama through poor romantic choices; his ex-wife Angela oscillates between supportive and chaotic. The show seems aware of these dynamics—it occasionally lets Moore land sharp, antiheroic beats—but awareness doesn't transform the underlying structure, which remains centered on male authority and male decision-making.

Sheridan's treatment of Indigenous history and presence is more indirect but no less troubling. Landman avoids the explicit Native storylines of Yellowstone or 1883, but that absence itself is telling. West Texas oil extraction has its own fraught history with Indigenous land and water rights, yet the show's moral universe erases those stakes entirely, treating the land as though it were neutrally available for extraction rather than contested territory with ongoing legal and environmental implications. Academic critics argue that Sheridan's transcultural metaphors—equating ranchers' "vanishing way of life" with Indigenous dispossession—risk flattening distinct histories into a generalized frontier nostalgia. Landman doesn't make that equation explicit, but by centering oil work as noble labor without interrogating land claims or environmental consequences, it participates in the same erasure.

Then there's violence. Sheridan's shows trade in spectacle—cartel executions, oilfield accidents, boardroom betrayals—rendered with prestige production values that make brutality visually arresting. Landman's Season 2 hydrogen sulfide disaster is gripping television, but it also exemplifies a pattern where workplace danger becomes aesthetic rather than systemic critique. The show acknowledges that oil work is deadly, but it frames that danger as proof of masculine toughness rather than as an indictment of industry safety standards or regulatory failure. Violence, in Sheridan's universe, is always individual—a choice, a risk, a test of character—never structural.

These criticisms don't render Landman unwatchable; they make it ideologically legible. The show knows what it's doing, and part of its appeal lies precisely in its willingness to indulge fantasies—of unfiltered speech, uncomplicated gender roles, resource extraction as patriotic service—that much of prestige television has complicated or rejected. Whether that indulgence is a feature or a flaw depends on where you're standing, which is exactly the point.

Figure 6: Season 2 promotional key art featuring silhouettes against massive oil rig flares—visual distillation of Landman's neo-Western industrial aesthetic. The burning flares evoke danger, chaos, and the environmental consequences the show acknowledges but rarely interrogates as systemic issues.

Figure 7: Thornton in intimate bar negotiation scene—characteristic of the show's focus on back-channel deals and masculine power dynamics. Landman frames these informal spaces as where real work happens, bypassing institutional channels the show codes as incompetent or corrupt.

Why It Works: The Strategic Ambiguity of Cross-Partisan Appeal

The paradox of Sheridan's success is that his shows are simultaneously read as "red America" entertainment and as complex enough to warrant serious critical engagement from coastal publications. Landman's 35 million viewers and Thornton's Golden Globe nomination suggest a reach that transcends narrow demographic targeting. So what explains the crossover appeal?

Part of the answer is craft. Thornton's performance is genuinely layered, toggling between weary pragmatism and alpha-male swagger with the kind of lived-in credibility that makes Tommy watchable even when his worldview grates. The show's production values—cinematography, sound design, the visceral staging of industrial accidents—meet prestige standards. Episode scripts mix soap opera mechanics with procedural detail, creating narrative momentum that survives its ideological work. Critics who dislike the show's politics often concede it's compulsively watchable, which matters more for audience retention than theoretical consistency.

Another factor is strategic ambiguity. Sheridan's shows offer enough textual openness that viewers with opposing politics can find validation. Progressives can watch Landman and see a critique of corporate greed and environmental recklessness; conservatives can see a defense of blue-collar labor and energy independence. Tommy's anti-renewables monologue can read as either satire or endorsement depending on the viewer's priors. This isn't accidental sloppiness—it's genre fluidity deployed as political hedge, letting the show function as a Rorschach test for American anxieties.

Then there's the anti-institutional stance. In a polarized era where trust in traditional institutions has collapsed across the spectrum, Landman's cynicism about bureaucracy, corporations, and regulatory agencies resonates everywhere. The show doesn't ask viewers to trust the system; it asks them to trust individuals navigating broken systems, which is a message that travels well in 2025. Tommy's competence fantasy—the man who knows how things really work, who can fix problems the official channels can't—appeals to anyone who feels alienated from centers of power, regardless of their partisan alignment.

Finally, Sheridan benefits from a cultural moment where prestige television's urban, progressive default has left a gap in the market. Landman doesn't apologize for centering white, male, working-class experience; it doesn't code that experience as retrograde or in need of correction. For audiences tired of being told their values are outdated, that representation alone is a form of respect. And for audiences who find Sheridan's politics troubling, the show still offers the pleasures of melodrama, strong performances, and a window into subcultures—oil extraction, cartel dynamics, Texas boomtowns—that prestige TV rarely depicts.

Figure 8: Formal portrait emphasizing Thornton's frontier iconography—Stetson hat, cream Western shirt, weathered authority. This visual presentation encodes the show's argument for uncomplicated masculinity and working-class authenticity that resonates across partisan divides.

Figure 9: Thornton and Demi Moore's Cami Miller walking through modern corporate space—frontier masculinity (cowboy hat, tan blazer) alongside contemporary female executive power (white blazer). The visual juxtaposition captures the show's gender tensions and generational conflicts.

What Landman Tells Us About Television and American Polarization

Landman Season 2 is not prestige television pretending to be populist; it's populist television executed at prestige scale. That distinction matters, because it clarifies what Sheridan's empire actually represents: a successful bet that television audiences are hungry for stories that center labor, distrust institutions, and treat land and resource control as moral imperatives rather than policy debates. Whether those stories are ideologically coherent is less important than whether they feel true to the anxieties of the moment—and by that measure, Landman succeeds.

The show arrives at an inflection point for streaming economics. Paramount+, under new ownership and chasing profitability, is banking heavily on Sheridan's ability to deliver reliable, appointment viewing that drives subscriptions. The strategy reflects a broader industry recognition that prestige credentials alone don't guarantee audience loyalty; that "flyover country" is not a monolith but a diverse, underserved market; and that political ambiguity can be as commercially valuable as political clarity.

But the cultural implications are more complicated than the business case. Landman's success suggests that television's role in American polarization isn't just about echo chambers or partisan messaging. It's about which experiences get centered, which values go unquestioned, and which anxieties get metabolized into entertainment. Sheridan's shows don't argue—they assert. They don't interrogate traditional masculinity or extractive industry—they validate them. And for millions of viewers, that validation feels like a corrective to a media landscape they experience as hostile or indifferent to their lives.

The danger, if there is one, isn't that Landman exists or that audiences love it. The danger is that it might be the only show of its kind that gets made at this scale, that Sheridan becomes the sole ambassador for an entire swath of American experience. Monoculture is the problem, not this particular culture. The more interesting question is whether other creators will find ways to tell working-class, resource-economy, red-state stories without replicating Sheridan's gender politics, his erasures, his anti-institutional cynicism. If Landman is the beginning of a conversation, that's useful. If it's the end of one, that's something else.

For now, Landman Season 2 does exactly what it set out to do: it entertains, it provokes, and it gives audiences a version of America that feels both familiar and aspirational, even when that aspiration is retrograde. Whether you find that thrilling or troubling probably says more about your politics than the show's. Which, again, is exactly the point.

Figure 10: Season 2 scene showing personal stakes alongside the show's blue-collar aesthetic. Landman balances corporate drama with family melodrama, though critics note the latter often reduces women to narrative complications rather than fully realized characters.