In the vast, sun-scorched expanse of West Texas, under a sky that stretches into an infinite blue, a modern-day archetype toils for the black gold that fuels the world. He is the roughneck, a figure as central to the mythology of Texas as the cowboy, yet often shrouded in a layer of crude oil and misunderstanding. As Taylor Sheridan’s series Landman drills into the high-stakes world of the Permian Basin, it brings this figure to the forefront—the man on the rig floor, the engine of the boom. To understand the world of Landman, one must first understand the life, the grit, and the unique culture of the roughneck. This is a world where physical endurance, unwavering brotherhood, and surprising faith converge in the dusty heart of the American energy landscape.

From Carnival Grounds to Derrick Floors: The Birth of the Roughneck

The term "roughneck" wasn't born in the oil patch. Its origins trace back to the traveling carnivals of the 19th century, a label for the tough manual laborers who did the heavy lifting. But as the 20th century dawned and a geyser of oil erupted at Spindletop in 1901, the term migrated and found its permanent home. That monumental strike near Beaumont, Texas, triggered a frenzy. Thousands of inexperienced farmers, dubbed "boll weevils" by seasoned workers, abandoned their fields for the promise of wealth bubbling from the ground.

In boomtowns that sprang up overnight—places like Kilgore, Wink, and Odessa—these greenhands learned the perilous trade. They learned to sling heavy tongs, connect lengths of steel pipe, and wrestle with machinery on the derrick floor. Once they had proven their mettle, covered in the mud and guts of the earth, they graduated from "boll weevil" to "roughneck." The name stuck, becoming a badge of honor for those who worked the rigs, a title synonymous with hard work, fortitude, and a certain kind of rugged individualism.

The Daily Grind: Sweat, Steel, and Sun

The life of a modern roughneck in the Permian Basin is one of relentless physical demand, governed by the unyielding needs of the rig. The day begins long before the Texas sun rises to its full, blistering peak. Mornings typically start around 5 a.m., preparing for shifts that stretch 12, sometimes 14, hours. There is no easing into the workday; it is full-throttle from the moment they step onto the rig floor. citation

The work itself is a symphony of coordinated, back-breaking labor. Roughnecks are the hands-on muscle of the drilling operation. Their tasks can include anything from connecting and disconnecting massive 30-foot sections of drill pipe—a process called "tripping"—to maintaining equipment, cleaning the rig floor, and assisting the driller. It's a job where "getting soaked with oil or blasted with mud is inevitable," as writer and former roughneck Christian Wallace described his experience. citation

The romanticized image of a shirtless worker splattered in crude is a relic of the past. Today, safety is paramount, though it comes at a cost. Workers are clad head-to-toe in thick, fire-retardant (FR) coveralls or jeans and shirts. This essential gear, designed to protect them from flash fires, ironically roasts them in the triple-digit Texas heat. The work is as filthy as ever, but the uniform has evolved to meet the constant threat of danger. citation

This grueling labor unfolds against the stark backdrop of the Permian Basin, a landscape transformed by the oil boom. So-called "man camps"—hastily built temporary housing complexes—have sprung up across the 75,000-square-mile region to accommodate the influx of workers. From a distance, the landscape is an industrial constellation of drilling rigs, droning pump jacks, and the perpetual flame of gas flares burning against the twilight sky. It is a frontier environment, isolated and immense, where the line between home and work blurs into a cycle of long hitches on the rig followed by precious time off. citation citation

The Brotherhood of the Rig

In an environment where a single misstep can cost a finger, a limb, or a life, trust is not a luxury; it is the most critical tool on the rig. This shared danger forges an intense bond among crew members, a unique form of camaraderie often described as a brotherhood. A drilling crew is a tightly knit team, a hierarchy built on experience and mutual reliance. The crew typically includes a driller (in charge of the rig floor), a derrickhand (who works high up on the derrick), a motorman, and several floorhands—the roughnecks. citation

Newcomers, often called "worms" or "green hands," start at the bottom, learning the ropes by observing, cleaning, and taking on the most menial tasks. They must prove their work ethic and reliability to earn the respect of the veteran hands. citation Effective communication and seamless teamwork are essential to perform tasks efficiently and, more importantly, safely. The crew functions as a single unit, each member anticipating the others' moves, their actions a well-rehearsed, high-stakes dance with heavy machinery.

This sense of brotherhood is the human element that makes the punishing conditions bearable. These men, from diverse backgrounds and different parts of the country, are drawn together by a shared purpose and a shared struggle. They work together, eat together, and often live in close quarters for weeks on end. This shared experience creates a support system in a place far from home, a family forged in steel and sweat. It’s a culture where you look out for the man next to you, because you know he’s looking out for you.

Faith in the Oil Patch: God, Grit, and Black Gold

The high-risk, high-stress nature of oil field work creates a unique spiritual environment. For many roughnecks, faith is not a Sunday affair but a daily reality, a source of strength and solace in the face of constant danger. The oil patch is a place of profound contrasts, where immense material wealth is extracted from the earth through life-threatening labor, and this tension often leads workers to seek a higher power.

This spiritual need has given rise to dedicated ministries. The Oilfield Christian Fellowship (OCF), a Texas-based organization, is one of the most prominent. Founded to serve the spiritual needs of workers right where they are, the OCF has expanded its reach from Houston to rigs and boomtowns across the globe. One of their most impactful initiatives is the distribution of "God's Word for the Oil Patch," a custom Bible that includes personal testimonies from people within the industry. citation

In the Permian Basin, the recent boom has been met with a spiritual one. Damian Barrett, who leads the Midland/Odessa chapter of the OCF, sees a "spiritual harvest" in the influx of workers. He keeps a trailer full of these specialized Bibles, ready to be distributed at rig sites and local businesses. The stories of their impact are powerful. Barrett recounted one instance where a worker took a Bible home, and both he and his wife read the Gospel of John that night. "We both got on our knees right there in the house and accepted Christ as our savior," the man told him. "And, we're changed." For these ministries, the payoff is "even better than the rich flow of oil and gas." citation

This intersection of gritty labor and deep faith is a defining characteristic of roughneck culture. In a profession where one is constantly reminded of their mortality, faith provides a framework for hope, purpose, and protection.

The Price of the Boom: High Wages and Heavy Sacrifices

What draws thousands of men to such a grueling and dangerous profession? The answer, overwhelmingly, is money. The oil boom offers the promise of high wages that are hard to find elsewhere, with many laborers earning six-figure salaries. This economic pull is powerful, attracting people from across the United States willing to trade physical hardship for financial security for their families. citation

However, this prosperity comes at a significant personal cost. The typical work schedule involves long "hitches," where a worker might be on-site for two, three, or even four weeks straight, followed by a week or two off. This rotational life creates a profound separation from family and home life. Birthdays, anniversaries, and holidays are often missed. The isolation of the man camp and the demanding work schedule can strain relationships and take a mental toll.

The physical price is equally steep. The oil and gas industry has one of the highest fatality rates of any profession in the United States. Workers face a daily barrage of hazards: the risk of being struck by heavy equipment, falls from heights, explosions, fires, and exposure to toxic chemicals like hydrogen sulfide gas. In the Permian Basin, more than two Texas workers die each month from such incidents. citation The roughneck life is a high-stakes gamble, weighing the potential for great reward against the ever-present risk of the ultimate sacrifice.

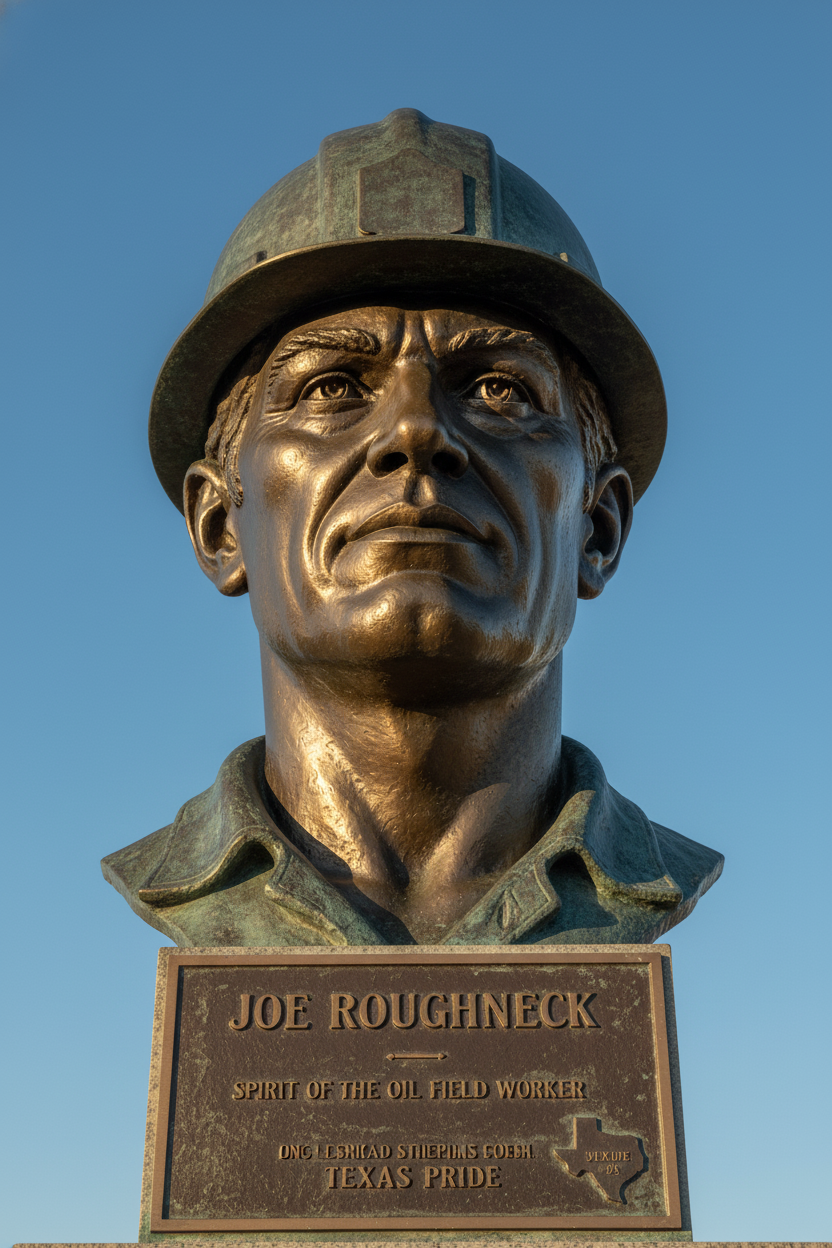

The Iconography of Grit: "Joe Roughneck" and Permian Pride

The figure of the roughneck has become a potent cultural symbol, representing the grit and determination at the heart of the American oil industry. Nowhere is this more evident than in the icon of "Joe Roughneck." Created in the 1950s, the sculpture of Joe Roughneck—with his square jaw "set to denote determination" and kind eyes—became the embodiment of the ideal oilman: "Rough and tough, sage and salty, capable and reliable, shrewd but honest." citation

Today, bronze monuments of Joe Roughneck stand proudly in several Texas oil towns, including Kilgore and Conroe, serving as memorials to the spirit of the workers who built the industry. This icon is more than just a statue; it's a validation of a tough identity, a symbol of pride for a workforce that often feels unseen by the wider world that depends on their labor.

This pride is also visible in the local culture of the Permian Basin. You see it on hats that say "Rig Daddy" and shirts that read "Permian Proud." citation It’s a culture that embraces its blue-collar roots and celebrates the hard work that fuels the regional and national economy. This identity, adopted by sports teams and immortalized in TV shows from Black Gold to Landman, solidifies the roughneck as a central character in the ongoing story of Texas.

Conclusion: The Heart of the Land

The West Texas roughneck stands at a unique crossroads of American identity. He is a laborer in a hyper-advanced industry, yet his work is primal and physically punishing. He is part of a global economic engine, yet he often lives in isolated, temporary communities. He faces down mortal danger daily, and in that crucible, often finds a deep and abiding faith.

As Christian Wallace writes after his own stint in the fields, "Texas is rich with oil, but it’s the blood and sweat of the roughneck that keeps it pumping." citation

They are the "motley crew of rascals and ruffians" who form the backbone of the boom, their lives a testament to the endurance, sacrifice, and unbreakable brotherhood forged in the heat and dust. Understanding their world—a complex tapestry of grit, faith, family, and fortune—is essential to understanding the very land and legacy that a series like Landman seeks to explore. They are not just characters in a story; they are the living, breathing heart of the oil patch.