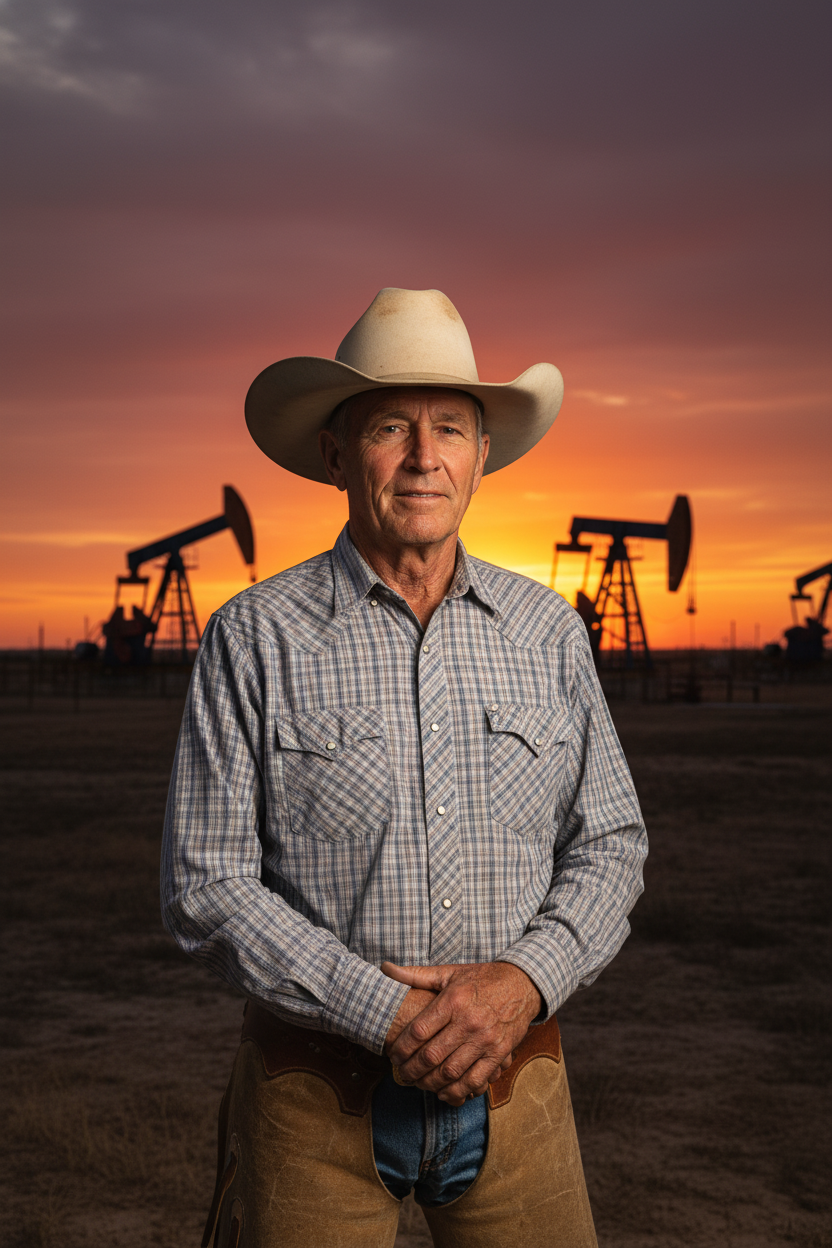

In the vast, arid landscapes of West Texas, the land lives a double life. By day, it is the domain of the cowboy, a world of sprawling ranches, grazing cattle, and a horizon defined by tradition and heritage. By night, under the flare of drilling rigs, it transforms into the dominion of the roughneck, a high-stakes industrial zone powering the global economy. These two foundational Texas identities, the rancher and the oilman, coexist on the same sun-scorched earth, often in an uneasy, contentious alliance. This collision of worlds, a central theme in Taylor Sheridan’s Landman, is not just fiction; it is the defining reality of the Permian Basin, a century-old conflict written into the very deeds of the land itself.

A Land of Cattle, Then a Sea of Oil

Before the first derricks pierced the sky, West Texas was cattle country. Following the Civil War, ranching empires were built on the seemingly endless open range. Families like the Waggoners, the Burnetts, and the Kings established legacies measured in land and livestock, their stories becoming integral to the Texas mythos. This was a life dictated by the seasons, the availability of water, and the price of beef. It was a hard, independent existence that forged a deep connection between the people and the land they stewarded. citation

Then, in the 1920s, everything changed. While drilling for water, wildcatters struck oil. The Santa Rita No. 1 well roared to life in Reagan County in 1923, revealing the Permian Basin, a subterranean sea of hydrocarbons that would prove to be one of the richest energy deposits on the planet. The discovery triggered a boom that dwarfed the Gold Rush. Overnight, the quiet ranching communities were inundated with oilmen, speculators, and roughnecks, all chasing "black gold." The region’s destiny was irrevocably altered, setting the stage for a hundred years of conflict and codependence between the world on the surface and the world below. citation

Today, the Permian Basin is an energy juggernaut, accounting for nearly 40% of all U.S. oil production and 15% of its natural gas. This boom has brought immense wealth and opportunity, but it has also placed an incredible strain on the traditional ranching way of life, turning pastoral landscapes into industrial zones and pitting neighbor against resource. citation

The Legal Quake: Texas's Dominant Mineral Estate

The heart of the conflict lies in a peculiarity of Texas property law: the "split estate." Unlike in many other places, Texas law allows the ownership of the surface of the land to be severed, or sold separately, from the ownership of the minerals beneath it. In oil-rich regions like the Permian Basin, it's estimated that over 95% of real estate is severed, meaning the person who owns the ranch often does not own the valuable oil and gas underneath. citation

Crucially, Texas law establishes the mineral estate as the "dominant estate." This legal principle gives the mineral owner (or the oil company they lease to) the implied right to use as much of the surface as is "reasonably necessary" to explore for, drill, and produce those minerals—without the surface owner's permission and often without direct compensation for the land use itself. This means an oil company can build roads, construct drilling pads, lay pipelines, and install storage tanks, all of which can disrupt or destroy ranching operations. For many ranchers, the discovery that they have little legal power to stop this activity on their own property is a shocking and infuriating revelation. citation

This legal framework, documented in complex leases and deeds, creates an inherent power imbalance. The surface owner, whose family may have worked the land for generations, is often left with limited recourse as the mineral owner's lessee industrializes their pastureland. This dynamic turns a simple ranch purchase into a complex legal gamble.

A Rancher's War: The Case of Antina Ranch

Nowhere is this conflict more starkly illustrated than in the story of Ashley Watt, a third-generation rancher who took on an oil supermajor. Watt’s family owns Antina Ranch, a sprawling property in West Texas where they have coexisted with the oil industry for decades. But in June 2021, an old, abandoned well—plugged decades earlier—began spewing toxic, super-saline water to the surface, poisoning the land and threatening the freshwater aquifer her cattle depend on. citation

Watt soon discovered this was not an isolated incident. Her ranch was pockmarked with dozens of old, improperly sealed "zombie wells" left behind by companies like Gulf Oil, now part of Chevron. These decaying wells were allegedly leaking methane and allowing highly corrosive produced water to migrate upwards, creating a subsurface environmental catastrophe. Faced with what she saw as corporate negligence and regulatory indifference, Watt did something few landowners have the resources or resolve to do: she sued Chevron, demanding they not just pay for damages, but clean up the century-old mess they inherited. citation

Her fight highlights a widespread problem. Across Texas, hundreds of thousands of old wells sit like ticking time bombs. Watt’s case has become a symbol of a growing landowner rebellion. As one legal expert noted, this is the reality that can turn "rock-ribbed conservative Republican ranchers" into "born-again environmentalists." When a 20-acre drilling site that was once prime grazing land is turned into an industrial zone of frac tanks, slush pits, and compressors, the abstract politics of environmentalism become deeply personal. citation

The "No Accommodation" Doctrine

For ranchers like Watt, the primary legal tool to protect their property is the "Accommodation Doctrine." This judicial principle requires the mineral lessee to accommodate the surface owner's existing uses (like ranching) if certain conditions are met. However, the burden of proof is entirely on the surface owner, and it's a notoriously difficult bar to clear. citation

To win, the rancher must prove three things:

- The oil company's operations will "substantially impair" their existing surface use.

- The rancher has "no reasonable alternative method" to continue their existing use.

- The oil company has "reasonable, industry-accepted alternatives" to access the minerals while still accommodating the surface use.

The second point is often the killer. In a key Texas Supreme Court case, a rancher argued that a proposed well site would interfere with his established cattle corrals. The court ruled against him, reasoning that he failed to prove he had no reasonable alternative because he could have built temporary pens elsewhere on his property, even at his own expense. This high threshold is why many oil and gas lawyers privately refer to the doctrine as the "No Accommodation Doctrine," as it provides little practical protection for landowners against the dominant mineral estate. citation

The Gilded Handcuffs: An Economic Lifeline

Given the legal imbalance and potential for destruction, why would any rancher consent to drilling? The answer is simple and complex: economic survival. Cattle ranching, while culturally iconic, is a risky, low-margin business. Drought, market fluctuations, and rising costs make it incredibly difficult to sustain a family, let alone a multi-generational legacy. citation

For many, the income from oil and gas leases is a financial lifeline. The bonus payments and royalty checks—a percentage of the revenue from produced oil and gas—can be the difference between keeping the ranch and selling it off. The Fisher family, owners of the century-old Bullhead Ranch in West Texas, is a prime example. The profits from their own oil wells are what enable them to keep the ranching tradition alive. In this way, the oil industry, while a threat to the ranching lifestyle, is also often its reluctant savior. citation This creates a deeply conflicted relationship, a set of "gilded handcuffs" where ranchers lease their land to the very industry that disrupts their way of life, simply to afford to continue that way of life.

A Way of Life Under Siege

The impact of the oil boom is more than just legal or economic; it's a fundamental assault on a culture. For a generational rancher, the land is not just an asset; it is their identity, their heritage, and their legacy. The industrialization of that land is a profound loss.

The boom transforms the sensory experience of the landscape. The quiet is shattered by the 24/7 roar of drilling rigs and compressor stations. The darkness is erased by the perpetual glow of gas flares. The empty county roads are clogged with heavy truck traffic, kicking up dust and tearing up the pavement. The very water that sustains life is under threat, both from overuse by fracking operations and from contamination by "produced water"—the toxic, salty brine that comes up with oil and gas. This wastewater is often reinjected deep underground, a practice now linked to a dramatic increase in earthquakes in a region that was historically seismically quiet. citation

For ranchers whose families have lived on this land for over a century, the change is heartbreaking. "God didn’t build the Garden of Eden out there in West Texas, but we’ve been making a living off of it for six generations now," one rancher told state regulators. "I know you think it’s just a wasteland, but we live out there." citation

Conclusion: An Unsettled Frontier

The story of West Texas is a story of two competing industries and two clashing identities locked in a forced, perpetual dance. There is no simple path forward. Some ranchers, like Ashley Watt, choose to fight, pouring their resources into litigation to demand accountability. Others, seeing the economic writing on the wall, embrace the oil income, using it to expand and modernize their ranching operations. Many more walk a difficult middle path, negotiating Surface Use Agreements (SUAs) to try and carve out some protection for their homes, water wells, and livestock, accepting the disruption as the price of survival.

This tense, symbiotic relationship is the dramatic core of the modern American West. It is a conflict over who controls the land, who profits from it, and whose way of life will endure. As Taylor Sheridan’s Landman explores, this is not a settled history but an active, ongoing struggle. The future of West Texas is being forged daily in courtrooms, in lease negotiations, and on the fencelines where the pasture meets the drilling pad. It remains an unsettled frontier, where the legacies of both the cowboy and the oilman hang in a delicate, precarious balance.